There are some things I really miss about running a newsdesk.

Rising to the challenge of a big, breaking story; the shared satisfaction of a job well done or a campaign well won; and motivating and mentoring my own little team of miracle-workers are the ones that spring to mind.

But there are a few more that I don’t miss in the slightest.

Regular weekend working, finding nibs for p29 of the Somerset Guardian on a Tuesday night – and second-guessing the audience.

It’s that last one which keeps editors, news editors, what’s on writers, and sports journalists – not to mention managing directors – up at night.

They’ll be checking Chartbeat – or whatever other site they use – last thing at night and first thing in the morning, risking the ire of partners in the search for reassurance that targets have been met.

Sometimes – a lot of the time – it can feel like mission impossible.

It was one of those times that led to this question being posed on Facebook by someone in a newsroom not a million miles from me:

What do people actually want to read about in the press?

I felt her pain.

There were some cracking contributions – some serious, some not so.

Perhaps the best combined both approaches:

The unbiased truth. And puppies.

Journalists have been searching for the holy grail of what readers really want for centuries.

After putting together a particularly splendid paper, I used to quote a then-not-yet-disgraced radio DJ, one of whose catchphrases was: “If this don’t turn them on, they ain’t got no switches.”

Those switches can be incredibly hard to find at times.

My best guess at a recipe for story success in the regional media has always involved a well-known community figure caught up in some kind of intrigue: an arrest, an emergency, an investigation.

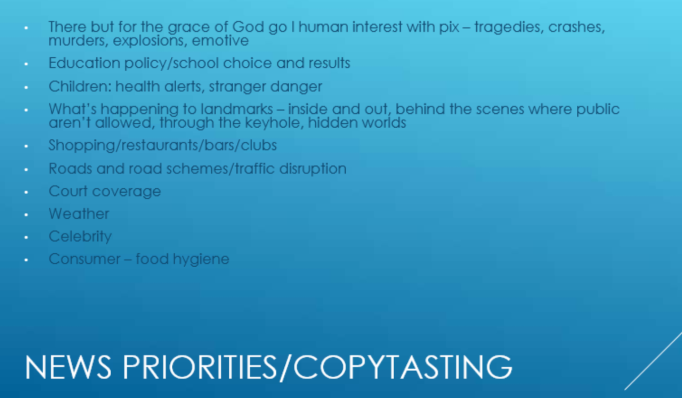

Failing that, there’s this little list I used to hawk around training sessions and the occasional lecture.

I like to think I wasn’t far off the great Harold Evans’s definition of what makes great news.

“News is people. It is people talking and people doing. Committees, cabinets and courts are people; so are fires, accidents and planning decisions. They are only news because they involve and affect people.”

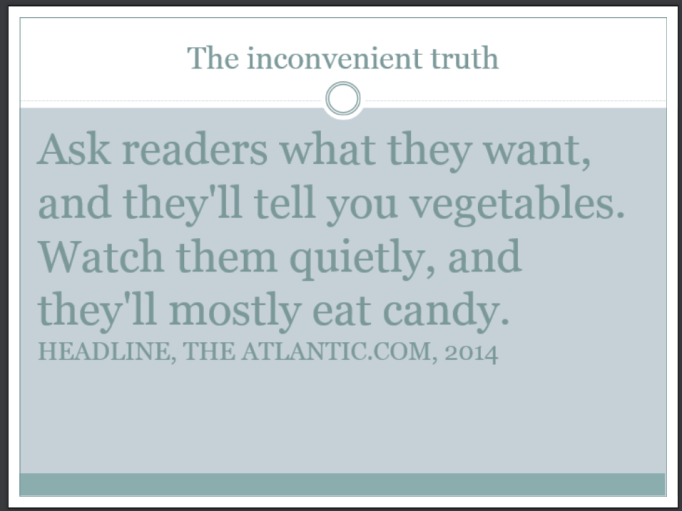

But those very people can be fickle. What they go for one day can flop spectacularly when served up on another.

Plus there’s always this little beauty to bear in mind.

Those bloody readers. Telling us they want more local news, telling us they want more good news, then posting smart-arse ‘slow news day?’ comments on Facebook when we try to respond.

But – as often happens – reassurance came in the form of Trinity Mirror digital publishing director David Higgerson’s latest blog on social media.

It was packed with examples of positive, heart-warming, good news stories that had really taken off on Facebook – from charity fundraising stunts through retiring police officers to one which simply reported that no horses had died at the Grand National.

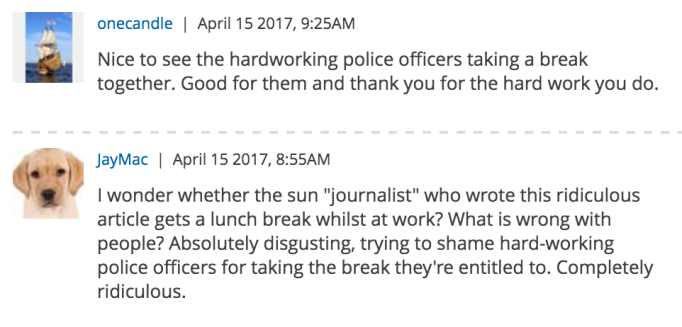

I was cheered also by the response on Facebook and from online commenters to the Plymouth Herald’s coverage of a literal storm in a coffee cup.

Not for the first time in the last week, there was no love lost for The Sun, which thought that a group of police officers having a coffee break was a story.

And finally came proof of something that I’m going to lazily call an old adage: that teachers learn at least as much from their students as students learn from them.

I stumbled across a blog from one of our third year students, which actually said what I had been trying to say. Only better.

Here’s our Sophie Jones:

“We consume the news that we want to consume and whether that’s good news, bad news or neutral is up to you to decide.”

In the end, perhaps, the Facebook algorithms and our own synapses combine to give us the news we deserve.

As Sophie so rightly suggests, it’s a state of mind. If we go looking for bad news, we’ll find it.

We’ll never entirely know what our readers want.

But, as journalists, we’re readers too.

And the more we go looking for good news, the more we might persuade others to do the same.