I don’t think I’ve ever seen Twitter so dominated by one story as it was this weekend.

I was at a gig on Saturday night, and all around us in the breaks were people coming to terms with the tragic death of TV presenter Caroline Flack.

I say coming to terms with. I could equally have said hungrily consuming news of.

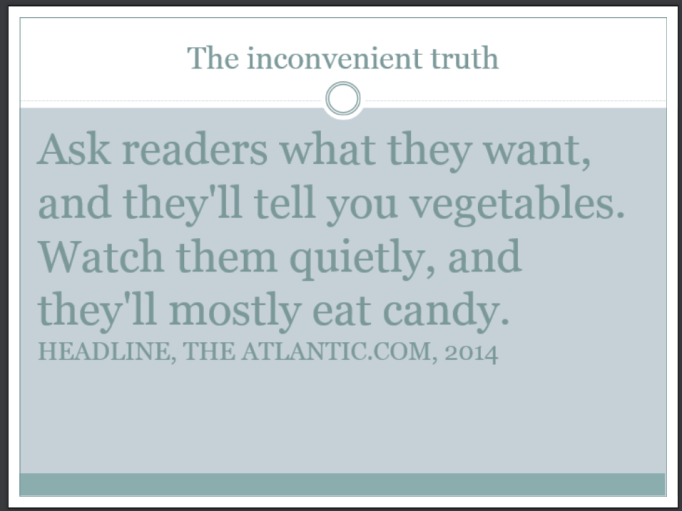

There’s a favourite phrase of mine from an American analysis of news habits: Ask people what they want, and they’ll say vegetables. Watch them, and they’ll be eating candy.

I promise you, journalists will stop writing about every cough and splutter about celebrities when people stop wanting to click and read it.

— Simon Neville (@SimonNeville) February 15, 2020

It’s easy and convenient to blame tabloid journalism for Flack’s suicide. And there’s little doubt that the relentless, dehumanising coverage of her very dramatic personal crisis will have played its part.

As many people have said – pointing to the Samaritans’ excellent guidance to reporters for suicide coverage, there is very rarely one single reason for someone taking their own life.

✅Some points frm @samaritans media guidance re celebrity suicide

✅The causes of suicide are never simple. Attributing blame is rarely helpful & can cause harm

✅Most people don’t act on suicidal thoughts. They are a sign that something needs to change- call Samaritans 116 123 pic.twitter.com/sTH5B19AhS

— Siobhán O’Neill (@profsiobhanon) February 16, 2020

It’s a point well made by media law expert David Banks in a calm thread on the subject.

The death of Caroline Flack is a tragedy for her family and those who loved her. There were a number of things happening in her life that we know a little about – the upcoming trial for assault; her relationship with her boyfriend; her removal as a presenter of Love Island…

— David Banks (@DBanksy) February 16, 2020

But that media coverage won’t have helped Flack’s mental state. And that coverage was there because there was an appetite for it.

And non-journalists – real people, with children and parents and jobs – weren’t just reading what the Sun and Mail Online served up. They were launching their own social media missiles – here at Flack, but on another day it would be someone else: Meghan Markle, Sam Smith, Jess Phillips, Laura Kuennsberg or Jameela Jamil.

I am a massive fan – and user – of Twitter. It makes me laugh, connects me with people doing the same work as me, alerts me to news stories, challenges my opinions, and warms my heart.

But it’s also a sewer of anonymous abuse, vicious views and pathetic paranoia.

That anonymity is a real issue. This is clearly not breaking news, but that identity cloak allows people to say things they wouldn’t dream of uttering to their target’s face, even if they had the cojones needed for such plain and honest speaking.

They wouldn’t say such things in front of their mums, either – an old school criticism, but perhaps a relevant one, given that many trolls undoubtedly still live with their mothers.

In the end, we are all to blame for Caroline Flack’s death.

There are public interest aspects here: she was a celebrity charged with a crime. There was every reason to cover her court case.

And, as the brilliant Secret Barrister has said, the Crown Prosecution Service had little option but to pursue the court action.

In other circumstances, dropping a prosecution at the request of the victim could be a slippery slope to condoning coercion.

A number of people have asked questions about the tragic case of Caroline Flack.

I have no particular insight into her case or her personal circumstances. But some general observations are set out below for assistance.

— The Secret Barrister (@BarristerSecret) February 16, 2020

Cases cannot be dropped simply because a complainant doesn’t want their partner prosecuted. Such a system would reward those who successfully coerce victims to withdraw. Sometimes cases must be pursued without the consent of the alleged victim.

But not always.

— The Secret Barrister (@BarristerSecret) February 16, 2020

But elements of the media – and as always, it’s crucial to remind the world that this is not some monolithic machine in which every journalist is the same – have behaved appallingly.

Bizarre night following news/social media from several time zones away. Not the most important thing tonight, but one lasting thought- ‘the media’ is not one body to be lambasted en masse, however much parts of it deserve it.

— Rob Freeman (@robglaws) February 16, 2020

Instead of shining a light upwards into the dark corners of authority, they have turned a dazzling spotlight downwards, onto a vulnerable woman, cataloguing and amplifying her spiral into despair and loneliness.

And the tragedy has sparked an interesting debate about the extent to which individual – perhaps fairly junior – reporters can be held responsible for the editorial decisions and policies of their titles.

This reporter is not responsible for the story. It is an editorial decison. If she hadn’t written it, someone else would have. Junior reporters don’t have much choice in what they write, esp at nationals. Don’t you see the irony in hounding an innocent woman? https://t.co/MNNTRBxy0o

— Alya Zayed (@alya_zyd) February 15, 2020

Like a lot of journalists, I feel conflicted whenever I criticise tabloids because I have friends who work on them who are good people. Sometimes I hope when I criticise the S*n or the Mail (which is almost daily) that people I know who work on those papers don’t see it

— Robyn Vinter (@RobynVinter) February 16, 2020

Like a lot of journalists, I feel conflicted whenever I criticise tabloids because I have friends who work on them who are good people. Sometimes I hope when I criticise the S*n or the Mail (which is almost daily) that people I know who work on those papers don’t see it

— Robyn Vinter (@RobynVinter) February 16, 2020

It’s not just the media, though.

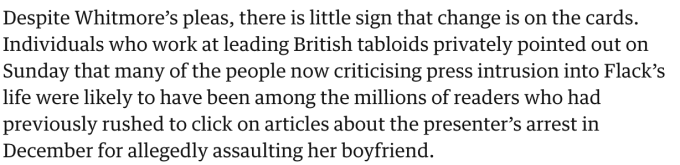

There’s a circuitious relationship between media and audience, and no doubt some people take their cue from what the Sun or Mail say or do.

But the media are also led by the attitudes of their readers.

And that’s us. And the way we behave.

After MP Jo Cox’s death, we all promised to be better.

If you did a word map of the terms I use on Twitter the most, I’m glad to say ‘proud’, ‘lovely’ and ‘love this’ would feature strongly.

But I’m guilty of writing some pretty horrible things about the Prime Minister and his colleagues – calling the cabinet ‘spineless’ within 24 hours of Flack’s death.

Clearly there’s a difference between me randomly castigating those who willingly put themselves up for high public office, and a nameless keyboard warrior threatening to rape a singer.

But is there?

We all need to look at ourselves in the mirror and question what we’re writing and saying on social media.

Flack’s last message to us all was ‘be kind’.

We should honour her memory by being just that.

And we should think long and hard about what two people who share the same Christian name said at the weekend.

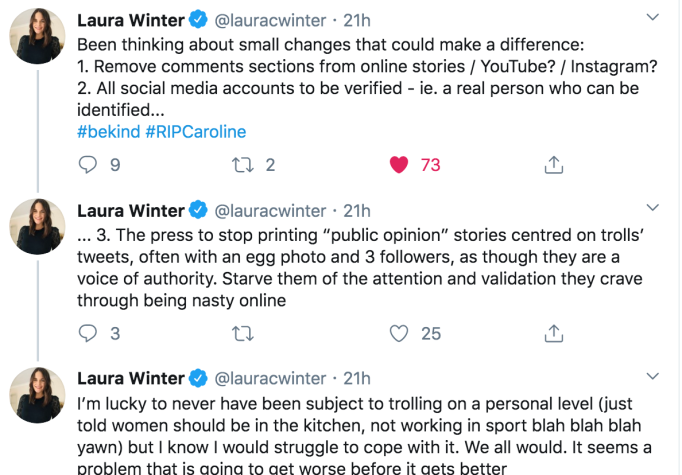

One of them I know: sports presenter Laura Winter, who’s been through the mill herself in recent times.

We have to force social media firms to move away from the anonymity that encourages the worst of human behaviour, and we as journalists have to stop using angry Twitter users as our touchstones.

And then there’s the other Laura. The one who valiantly went on air yesterday to give her own listeners a beautiful piece of her mind, speaking as Flack’s friend and successor on Love Island.

There are no better words than Laura Whitmore’s to sum up what we should all take away from the mad, sad tragedy of this weekend.

“So to listeners – be kind. Only you are responsible for how you treat others and what you put out in the world.”