The garden’s looking nice today, washed by much-needed rain. The washing’s on, I’ve made my hard-working uni student daughter a drink, and I’ve distracted myself a bit on YouTube.

If you need a break, or a bit of a lift, this morning, cop a load of this. Mel C and Emma B knocking out I Know Him So Well – culminating in the sort of hug we all yearn for in these times. https://t.co/oTNaF7E3wB pic.twitter.com/KMlk25Mx2i

— Paul Wiltshire (@Paulwiltshire) April 17, 2020

My dining room table now doubles as my office, as well as the venue for virtual pub quizzes, Zoom drinks and family Facebook Messenger video catch-ups.

As I write this, I’m consciously pushing my back into the dining room chair to adopt a better posture.

The move to home working happened pretty quickly. One of my colleagues left his glasses in our office – but luckily I was able to post them to him. I didn’t think to put my office chair in the boot of my car – I just overwatered my massive pot plant, locked the door and hoped for the best.

But one of my friends who news-edits a daily paper and website did – and it wasn’t just the chair. His monitor and keyboard went too.

A question now playing on the minds of almost every journalist I know is whether my friend’s chair – and thousands of others like it – will ever return to their original homes.

Most non-broadcast news organisations have been completely #wfh for around a month now – and there’s increasingly plenty of radio and TV people now operating in the same way.

It’s not the same, clearly.

Anyone’s who’s ever been responsible for district office reporters will know the tricky choreography of keeping in contact with staff that you can’t just chat over the desk to. Minor requests can suddenly seem like a big deal, misunderstandings creep in, and a them and us mentality can take hold in the absence of making-the-world-go-round natural office chat.

Those virtual team chats can be disjointed and superficial if we’re not careful.

And yet, there are upsides. Another friend, working for another daily publication, is loving the fact that his commute is now measured in seconds rather than hours.

And I don’t think I’m going all ridiculously and naively hearts and flowers when I say that, with the right effort, video chats can be just as warm, bonding and satisfying as some face-to-face exchanges. Perhaps it’s because you’re consciously setting aside time for them. I certainly don’t feel any less connected with colleagues and – more importantly – my students. Video personal tutor catch-ups are for the most part a complete joy, and I’ve never yet clicked the phone icon to close a call without feeling better about life.

One of the most heartfelt but ultimately meaningless phrases we now use is ‘when this is all over’, or ‘when we get back to normal.’

It’s crystal clear we’re not going to be able to flick a switch and return immediately to the old world. It’s going to be messy, it’s going to be long – and it’s going to be painful.

Press Gazette today reports that 2,000 media jobs have already been affected by the coronavirus crisis, with advertising income in tatters, and huge segments of journalistic life closed down.

The jobs that have been cut, the publications that have been suspended, and the staff that have been furloughed will not simply bounce back in three months’ time.

I’ve often said that – from a loss of titles and coverage point of view, the public never know what they’ve got till it’s gone.

But it’s equally true that, from the point of view of managing a business, you can only really judge how vital some things are when you have to live without them.

I’ve long been concerned at the erosion of newspaper offices, and was initially alarmed at the acceleration of closures in some parts of the south west.

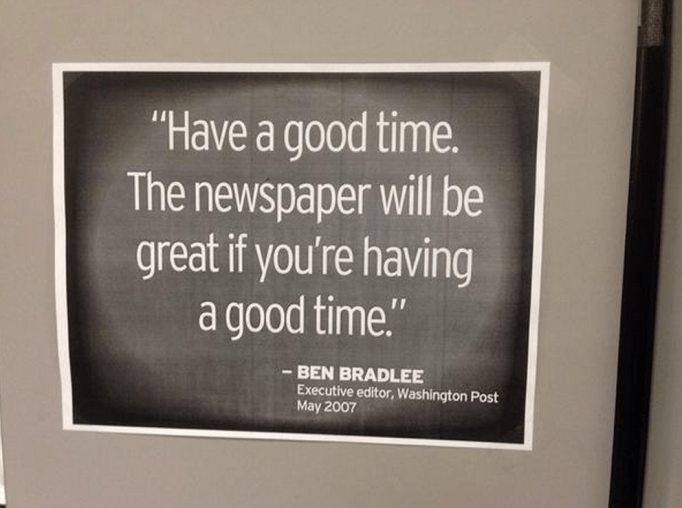

There’s something hugely special about newsrooms, particularly those in quaint buildings at the heart of town or city centres.

There’s also something magical that you can’t put a financial figure on about the craik, the camaraderie and the creativity that comes from forcing journalists into the same room.

Journalism is a team game – and I’ve always thought it’s played best when you’re literally standing (or sitting) shoulder to shoulder with your team-mates.

But in a once-in-a-century earthquake like this, can we afford all that bricks and mortar?

I’ve been intrigued by the work of a business called Fathm, which helps newsrooms adapt to what it calls distributed working.

The argument is that, done correctly, having your workforce operating semi-independently from home can boost both creativity and audience engagement, and perhaps get people closer to their communities and readers.

In an uncertain world, one of the few things of which we can be absolutely sure is that life is never going to be the same again.

The industry – and not just the media, but the PR sector, too – will be looking for ways of saving money.

As always, I’d rather those ways involved buildings than people.

This is the acceleration of a sea change in the way journalism is organised.

It’s important that the captains are looking in the right places for ways to ensure that the things that get journalists out of bed in the mornings are still there when that bed is a matter of yards from the office rather than miles.

To continue my messy mix of maritime metaphors, we must make sure that the babies of camaraderie, community and creativity aren’t thrown out with the bathwater of any move to greater home working.