It stood there gleaming in the office kitchen.

All shiny and new, it had no visible buttons or levers.

But this was the machine that was going to make me – and my colleagues for the week of my latest Work Experience for the Elderly – a cup of coffee.

Eventually I got to grips with the hover technique needed to operate this smartest of smart taps.

After nearly flooding the newsroom kitchen in the process, I tweeted like a grumpy old man.

What’s wrong with kettles, I asked in confected rage.

‘You should write a first-person piece,’ one office wag said. ‘I tried the new tap in the kitchen and this is what happened.’

I declined the offer.

But it was a bit of a standing joke that virtually every experience any journalist ever has could be material for such an article.

You don’t have to look far to find reporters writing about everything from giant burgers to food shopping and from transport services to unusual costumes.

Some of the ideas look like they’ve unaccountably survived Alan Partridge’s Monkey Tennis process, while others are genuinely inspired.

My London lifestyle reporter Amber-Louise Large found herself the butt of sarcasm on Twitter this week over the subject matter of some of her pieces.

But – the occasional slightly patronising headline aside – there was some great content.

I absolutely love the process of finding new things to write about – of panning through the mud of rubbish suggestions to find the nuggets of gold.

So her piece on how long it takes for an all-white outfit to get dirty on an average day in the capital was genuinely refreshing.

I’d have been proud if one of our students pitched that at a news day.

Now that can’t be all a newsroom does.

There are stories to be told, and wrongs to be righted at every turn.

And, having spent a number of days in various newsrooms this summer, I’m under no illusions as to how difficult it can be to do challenging, time-consuming journalism.

You can see that today with the closure of The National Wales, an experiment launched with spirit and chutzpah by one of my favourite editors, Gavin Thompson.

But if there is one thing I know, it is that journalists have to be visible.

And Amber is certainly that.

The new Google regime is rightly forcing newsrooms to prioritise new, original and genuinely useful content.

So doing exactly the same as everyone else isn’t going to cut the mustard for much longer.

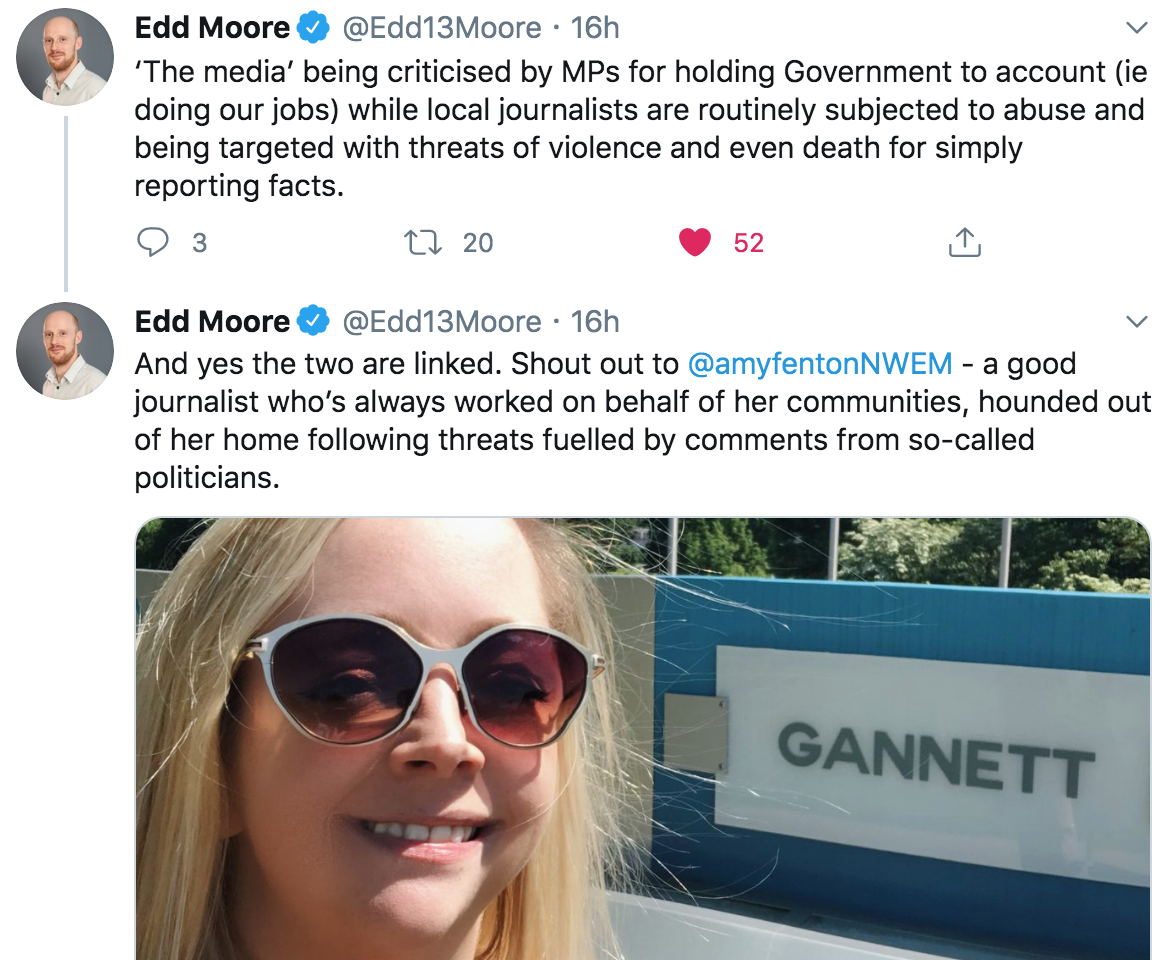

That ought to present newsrooms with a fantastic challenge at a time when politicians such as Liz Truss are keener than ever to undermine a media that holds power to account.

Like a pound shop Trump, she is never more pleased than when she hears people say ‘I don’t know who to believe any more.’

It’s a challenge taken up by the brilliant-looking new News Futures project at UCLAN, and one at the very centre of the wonderful MacTaggart lecture by Emily Maitlis.

One of her action points for the future for our industry is to for it to show its workings more – to explain why we do things, and how governments can make life unjustifiably difficult for us.

In a smaller way, that means editors and journalists meeting their audiences – ideally face to face.

I’ve visited two newsrooms in the last week which are geographically absolutely at the heart of the communities they serve.

We’ve also seen a newspaper get coverage of tragedy pitch-perfect in Liverpool.

All of that matters.

I am unashamedly a stuck record on this subject, and have been for many years.

We are never going to shift the dial on trust in journalism until more people actually knowingly breathe the same oxygen as a journalist.

If those first person pieces are getting journalists out of their offices and out of their spare bedrooms, that’s a small step in the right direction.

But it must lead to constructive engagement, too.

The goal must be for more of the public to come into meaningful contact with the newsgathering process – and for them to realise that it isn’t a machine, but actually real human beings doing their best to do a good job.

When more people realise they can achieve positive change in their communities in partnership with their local media, we will have begun to turn a corner.

And I’ll raise a battered newsroom Sports Direct mug of tea to that.